Lyme disease is the fastest-spreading vector-borne disease in the United States, with more than 400,000 estimated cases diagnosed annually. Lyme disease has been reported in every state in the United States.

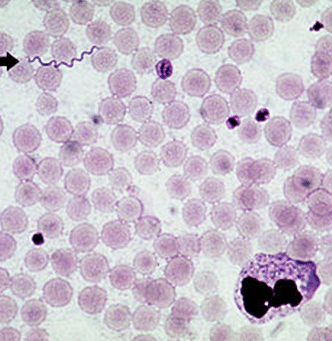

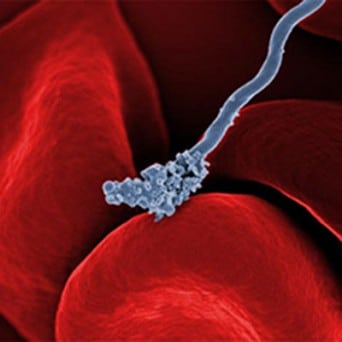

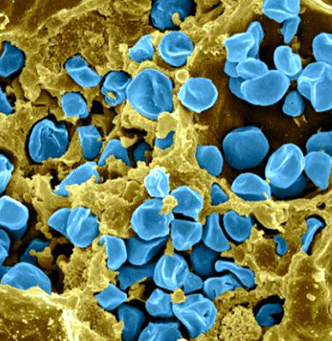

People contract Lyme disease and related co-infections from the bite of an infected tick. The tick becomes infected when it bites an animal that is carrying the infectious bacteria. Then, the tick transmits the bacteria through attachment to a “host,” such as a deer, pet, or person. Ticks are infectious in all stages of their growth cycle, but thought to be most dangerous in the nymph stage, as it may not be seen easily after it attaches to the host.

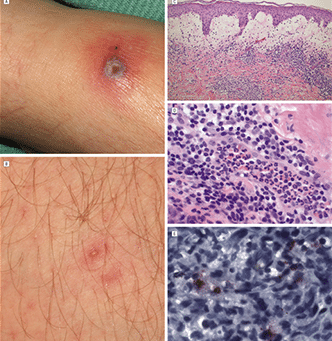

Some, but not all, patients manifest a bulls-eye’s rash associated with their tick bite, which is an early warning to seek medical treatment. However, a bulls-eye’s rash always indicates exposure to Lyme disease. When diagnosed early and treated aggressively, antibiotic treatment can be effective. Other cases that remain untreated for more than a month or two may require a longer duration of antibiotic therapy or other protocols to permit patients to regain their health. Unfortunately, even patients who develop the rash do not always receive correct medical treatment.

Why Patients Don’t Receive Correct Medical Treatment

Lyme Mimics Other Diseases

Medical studies have concluded that Lyme disease imitates symptoms of many serious conditions, including multiple sclerosis, ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease), Lupus, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and autism. Confusion with these conditions, in addition to Lyme’s association with chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, poor concentration, and memory problems further obstructs accurate diagnosis. Misdiagnosis may delay proper treatment and has been proven to be seriously detrimental to patient health.

Learn more about Lyme disease symptoms.

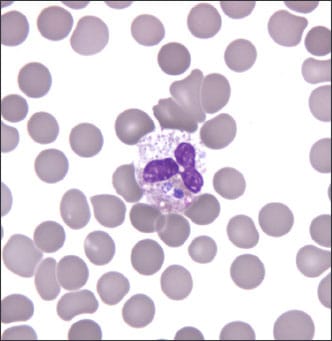

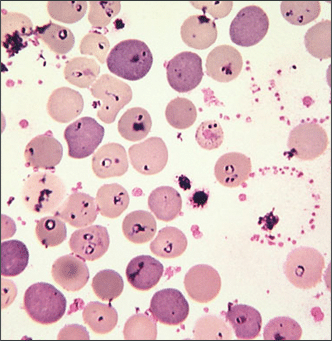

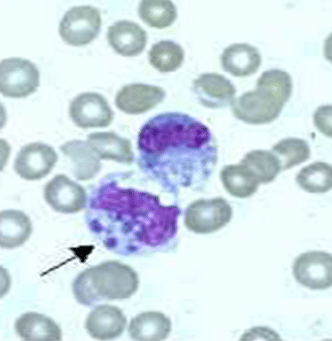

Testing is Unreliable

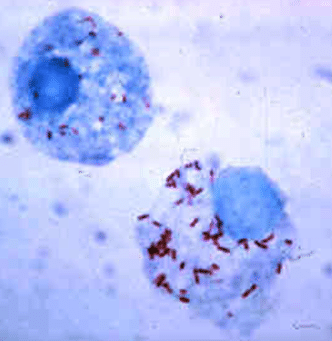

Diagnostic tests for Lyme disease are notoriously unreliable, resulting in false negative and false positive results. Doctors commonly adopt a two-tiered approach to testing for Lyme, so that if the first tier-test, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), results are positive, further testing with the more specific and accurate laboratory technique known as immunoblotting is used. This “Western blot” test identifies specific antibody proteins found in Lyme disease. In 2013 in Virginia, the Lyme Disease Information Disclosure Act highlighted the fact that a negative ELISA test does not necessarily mean you do not have Lyme disease.

Controversy within the Medical Community

Debate and controversy within the medical community may further impede and delay both accurate diagnosis and treatment of Lyme-related illnesses. Questions about whether a patient’s symptoms are due to Lyme or another disease, concern about the overuse of antibiotics, and the question of whether persistent or chronic Lyme actually exists are issues that have affected the timely treatment of Lyme patients.

When the Lyme infection persists, the original flu-like symptoms are often replaced with a myriad of other symptoms that can include fatigue, Bell’s palsy, sore and swollen joints, body aches, pain, severe headaches, swollen lymph nodes, cognitive impairment, and other neurological and cardiologic problems. When symptoms are not fully resolved after a short course of antibiotics, patients and their doctors commonly face additional treatment challenges. Some doctors refer to these persisting symptoms as “post-Lyme syndrome,” and prescribe symptomatic relief, including painkillers and anti-depressants, which do little to resolve what is possibly an ongoing infection.

Many practitioners have documented excellent, long-term results and a return to healthy functioning from extended antibiotic use. Conversely, other practitioners report that their patients improve with extended antibiotic therapy, only to relapse when treatment is withdrawn. They believe that this evidence shows that Lyme disease is a persistent infection that can elude standard courses of antibiotics.

The medical community’s division over the cause and cure of persistent Lyme disease symptoms illustrates the indisputable and immediate need for unbiased research. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) organized a workshop* in 2010 in an effort to begin the process of resolving these complex issues. Science journalist and author, Pam Weintraub, noted at the workshop, “If we are ever to unravel the mysteries of Lyme disease and find a cure, it is science ̶ pure and unadulterated ̶ that will lead us home.”

Due to the unrelenting efforts of people who are seeking a cure to this epidemic, many research efforts are underway today to improve testing and diagnosis as well as treatments for Lyme and associated diseases.

* Reference to, “Critical Needs and Gaps in Understanding Prevention, Amelioration, and Resolution of Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases,” by Institute of Medicine of National Academies.